STAY CURIOUS

Keep reading to find the excellency out of perfection and skill.

By: Milestone 101 /

2026-01-05

bollywood

Censorship After a Century: Why ‘Battleship Potemkin’ Stirred Trouble at IFFK

A century-old film becomes a contemporary flashpoint as Battleship Potemkin faces clearance hurdles at IFFK 2025. This article examines how modern censorship works through permissions, not bans, revealing shifting power over cultural spaces, film festivals, and political expression in India.

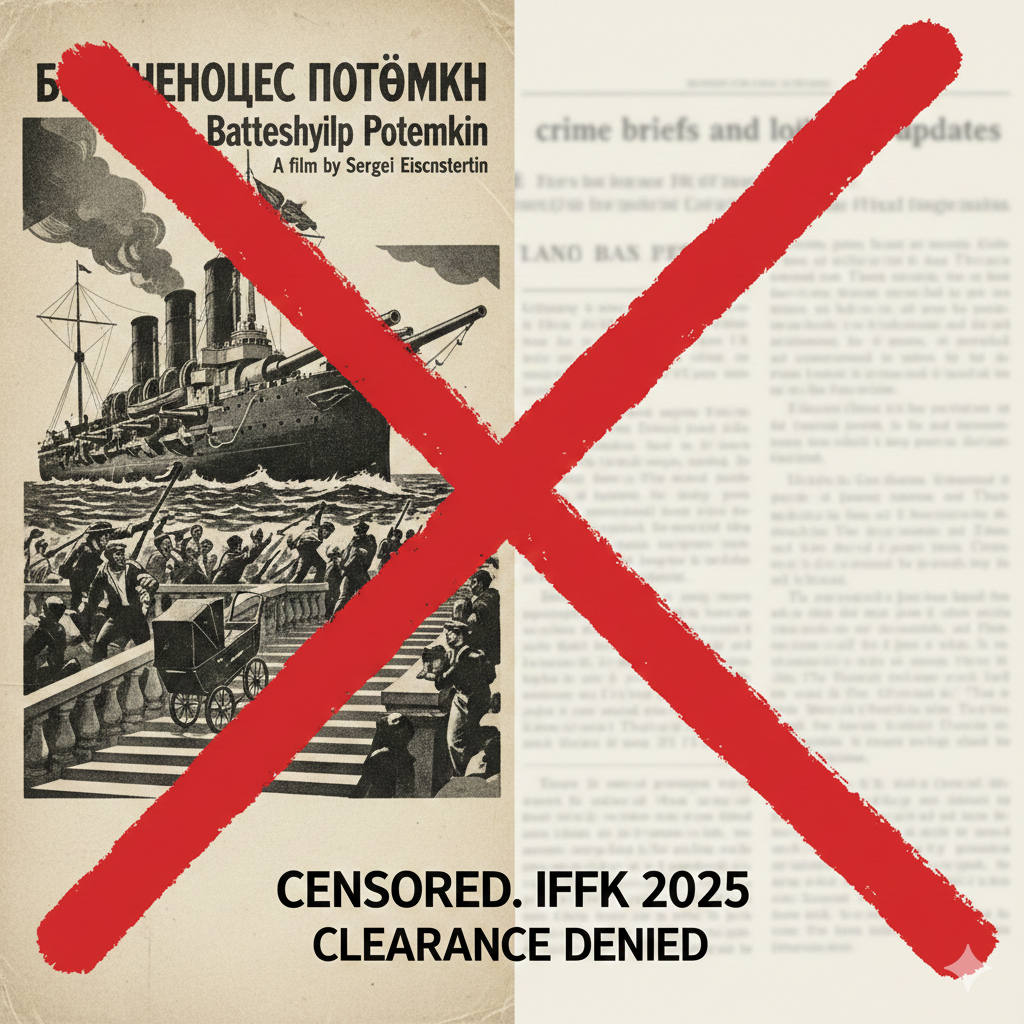

A century after its release, a silent black-and-white Soviet film found itself sharing front-page space with crime briefs and local political updates in a Kerala newspaper, not as a retrospective triumph but as a problem to be managed. The headline flagged a “crisis” at the International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK), and there, almost absurdly, sat Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin —a film long absorbed into global film culture—listed alongside Palestine titles and contemporary political cinema caught in a bureaucratic crossfire. The juxtaposition is jarring: a century-old classic, taught in universities and archived in museums, reduced to a line item in a clearance dispute, sandwiched between the everyday machinery of law and order and state politics. It reads less like a cultural celebration and more like an administrative crime scene.

Inside the Film Festival, this 'abusing' translates into 'distracting'. Delegates, who had booked and purchased flight passes, arrived in Thiruvananthapuram for a week full of intensely curated Screenings and found, instead, shows cancelled, vacant slots, and a swarm of volunteers attempting to explain why films that had travelled the world could not be screened in a place well known for 'Cinephile Culture'. This year was not a courtroom confrontation or Great Public Ban; this was a subtle form of interruption: censor exemptions withheld, schedules disorganised, and the Festival was forced to create on the fly, adapting to invisible decisions made by others. The result was the disarraying of established ritual; this annual 'Cinephile Pilgrimage' was an exploration of the fragility of Cultural Space, where access to cultural materials depends on permissions that could be delayed, denied, or selectively granted.

The centre of this disarray presents a paradox: How can Battleship Potemkin - a film that has withstood czarist censorship, scrutiny during the Cold War, and 100 years of global distribution - suddenly be labelled 'sensitive' at a contemporary Indian Film Festival? The film itself has not altered; there has been a substantial change in the systems by which films are chosen and made available to the public.

Potemkin As Idea, Not Artefact

To understand why this matters, Battleship Potemkin has to be approached not as a nostalgic relic but as a living language inscribed in the DNA of cinema. When Eisenstein formulated his theory of montage, he was not merely cutting shots together; he argued that juxtaposition itself could generate new meaning, that the collision of images could think politically. The film’s mutiny narrative—sailors rebelling against unjust officers—was explicitly revolutionary, but its enduring power lies in how it made editing a form of argument rather than mere continuity.

The Odessa Steps sequence exemplifies the evolution of cinema from simply creating a visual image into a tool for conveying information and emotion through a specific visual language that has enabled filmmakers, past and present, to create emotional connections with viewers. Studios such as Paramount Pictures have continued to reaffirm this particular visual language through their production of films such as "Psycho", and ultimately developed into the "Jaws", "Scarface", and "Godfather" series of films created by Francis Ford Coppola.

The film has consistently enjoyed a reputation as a "greatest film" in modern cinema, and filmmakers around the world have utilised it as a guide for shooting techniques and design, and as a reference point for examining the emotional impact and the connection between the filmmaker and the audience. In film schools, it remains a key element of film studies, with students dissecting the film to understand its cinematography; festivals using it to mark centenary celebrations; and digital and electronic formats allowing the film to reach homes and educational institutions worldwide.

In many contexts today, Battleship Potemkin is encountered less as immediate political agitation and more as history, pedagogy, and form.

That does not erase its revolutionary origins, but it shifts its function. In 2025, a centenary screening of Potemkin is less likely to incite mutiny than to provoke analysis of how images persuade, how power is represented, and how aesthetic innovation can emerge from ideological projects. Its power is now primarily analytical, not incendiary. Which is precisely what makes its sudden classification as “sensitive” at IFFK so revealing: the discomfort is not with a live political threat from a silent classic, but with the idea that specific histories, symbols, and alignments can still unsettle contemporary narratives, even in the safe space of a festival.

What Happened At IFFK?

The disruption at IFFK in 2025 did not announce itself as a ban; it arrived as an absence of permission. Under current Indian practice, films screened at festivals do not need a theatrical certificate from the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC. Still, they do require an exemption from the Union Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (I&B) if they have not already been certified. For years, this exemption process has been largely procedural, a backend ritual that allowed festivals to function as relatively autonomous zones of curated cinema.

This year's film exemption process changed drastically from previous years. Of the 206 submissions for exemption, the Ministry denied permission for a record 19 films, according to festival organisers. Many of the titles that were blacklisted were Palestinian films, including Palestine 36, Once Upon a Time in Gaza, All That Is Left of You, and Wajib, as well as other politically charged films like Battleship Potemkin, Hour Of The Furnaces, Timbuktu, Bamako, Clash, and Yes. In addition to these films, there was even a Spanish film titled Beef, a story about a rapper with no ties to its controversial title, which was blacklisted.

The timing of these denials only compounded the adverse effects on the festival, since the event was already being held in Thiruvananthapuram from Dec. 12-19 when the organisers learned that the 19 films had not been approved. Festival Vice-Chairperson Cuckoo Parameswaran said that 187 films were submitted for exemption. The lack of exemptions for the remaining films led to the cancellation of at least nine screenings on December 15 alone, and many more in the days around that date. Delegates who had planned their schedules around those films, many from other states and countries, were left with unfilled slots and quickly repositioned schedules, with very little explanation beyond the vague “no clearance” label affixed to the films.

The key to understanding this lies in the distinction between theatrical certification and festival exemptions. A CBFC certificate determines whether and how a film can be commercially exhibited to the general public across India; it is a gate to the marketplace. Festival exemptions, by contrast, are targeted permissions that allow non-certified films—including classics, restorations, and politically sensitive works—to be screened in a limited, curated environment to a registered audience. When the state withholds that narrower exemption, it does not formally “ban” a film; it simply ensures that a particular screening in a specific moment cannot take place. The result at IFFK was not open confrontation but paralysis: organisers caught between their commitment to the programme, the legal risks of defiance, and the logistical spiral of last-minute cancellations.

Selective Sensitivity And The Politics Of Permission

The films at IFFK being blocked show that this is more about being selectively sensitive to particular issues rather than to technical ones. Why were these films blocked? Why are they being blocked now? Why at a film festival? The clustering of Palestinian titles provides an immediate explanation for this. Titles such as Palestine 36, Once Upon A Time in Gaza, All That Is Left Of You and Wajib deal with occupation, dispossession, and the daily experience of living in a context of conflict that has become a part of the recent political discourse in India, coinciding with an increase of overt support from the Indian government to Israel in diplomacy and military matters. The screening of these films at a large public film festival such as this one in Kerala (where there is historical sympathy for Palestinians) can be seen as allowing another form of internationalism to present on an officially supported platform alongside First World countries.

In addition, the festival featured "Yes" from Nadav Lapid, an Israeli director who publicly condemned "The Kashmir Files" as vulgar propaganda during his time as chair of the jury for the International Film Festival of India in 2022, which makes the discomfort even more palpable.

The blocklist also includes works such as The Hour of the Furnaces, a landmark essay-film on anti-colonial struggle in Latin America, and Abderrahmane Sissako’s Timbuktu and Bamako, which examine jihadist rule and international financial institutions, respectively. Together, they form a loose constellation of films that foreground state violence, global injustice, and resistance.

What emerges is not a blanket prohibition of political cinema—many politically charged films did screen at IFFK—but rather a targeted friction applied to titles whose geopolitical and symbolic resonances intersect awkwardly with current state priorities. “Context” becomes a moving target: Palestine is sensitive because of foreign policy calculations; Lapid is sensitive because of his past criticism; Soviet revolutionary imagery is sensitive because it risks being read as legitimising revolt in a polarised domestic environment. None of this is spelt out; it is inferred from which films encounter bureaucratic drag.

This represents a significant shift in how censorship operates, according to many within the film industry. Veteran filmmaker Adoor Gopalakrishnan called the action "ignorant" because many classics, such as Battleship Potemkin, are found in homes and online and used by film schools as standard texts for film language. According to festival directors quoted by various media outlets, the practical repercussions of banning these films are immediate: festivals have had to cancel events, delegates have been disappointed, and the honouring of a filmmaker like Sissako, whose two crucial works were censored, has left them red-faced.

Political commentators have added to this perspective, with leaders like Shashi Tharoor condemning the censorship as overstepping the Government of India's bounds and harming India's cultural reputation. They have called on the Central Government to remove the effective ban and allow the festival's curation to continue. Cultural commentators are describing this incident as indicative of a larger trend in which perspectives that differ from or cause discomfort are not necessarily banned; however, their presentation is often complicated or delayed by excessive bureaucracy or frightful wartime prudence. Banning a film outright is not always the goal of this effort; the goal is to make it difficult for an institution to present it to the public, so that the institution will think twice before programming it.

Film festivals are often susceptible to this kind of strategy because they sit between culture, government, and funding systems. They are subject to clearances, logistically coordinating all aspects of the festival, and are generally financed in part through taxpayer dollars. If there is a delay in receipt of exemption request(s), or if the government issues a caution regarding potential violations of the Cinematograph Act, or a statement that some future monetary assistance may not be provided, then it will create a sense of caution in the festival organisers, without requiring that they receive any formal statement saying, "Do not show this film". Therefore, the politics of permission operate more through processes that require effort on the part of the organisers than through an outright prohibition on showing the film. Rather than stating, "You cannot show this film," they are conveying to the curator that "You can show this film, but you must be prepared for uncertainty, possible financial loss and potential legal danger."

The Kerala Factor: Culture Versus Compliance

Because IFFK – or the International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) – is not just a film festival, it’s about Kerala’s cultural identity. After over 30 years of growth as a festival with 10,000-15,000 delegates per year from the Kerala region, and having exposed generations of filmmakers and cinephiles to this region's film society and leftist tendencies in cultural contexts, IFFK has established itself as one of the most significant events in Kerala.

The history of IFFK was also taken into consideration when the Kerala government first responded to the news of the 19 films that had not received exemption. Instead of cancelling the screenings, the Kerala government instructed the Kerala State Chalachitra Academy to continue with all screenings, citing that the Centre’s intervention was an interference with state cultural autonomy and federalism. There was a brief opportunity for IFFK to serve as the major theatre for Kerala’s ability to operate and manage its own film festival independent of the National Government's oversight.

The conflict between the state and central governments quickly became mired in legal complexities. After the Union Ministry's warnings about the possible enforcement of other provisions of the Cinematograph Act against films shown without certification, Kerala had no choice but to change its stance and agree to screen only certified films. Resul Pookutty, chairperson of the Chalachitra Academy, stated that screenings should also take into account India’s global status, which sparked great outrage from filmmakers and critics over the decision to outsource screening policy-making to purely external factors.

A hybrid mix of these conflicting ideologies is created, which does not yield a straightforward, clear-cut narrative of the heroic act of resistance. Politically, the political leaders and government of Kerala made public statements denouncing the actions of the Centre and emphasizing the role of the IFFK as a democratic pluralist. However, from a practical standpoint, the festival complied with many of the Centre's decisions regarding the films with the most contentious views, signalling how much diminished state autonomy is possible under the layers of national-level legislation and central government approvals needed to conduct film festival operations. While the question remains whether a film festival can genuinely claim to operate independently, at least to any degree, when its ability to screen specific films relies upon obtaining last-minute clearances/approvals from the Government of India, regardless of its progressive organising philosophy, this remains a serious dilemma for film festival organisers within the Indian film festival system.

Who Controls Cultural Spaces In India Today

The episode at IFFK is an example of how, in India, control over cultural environments is increasingly exercised through access to those environments, rather than through large-scale bans. Film festivals are in a somewhat strange category: they are semi-public spaces open to many registered participants, frequently financed by the government, yet curated by festival organisers as venues for displaying more ‘out-there’ artistic work than a multiplex would typically show. In theory, film festivals provide an open space for creative expression; however, in practice, they are governed by multiple layers of permissions and security protocols, shaped by political sensitivities.

Film festival life creates the illusion of openness through the visual spectacle and trappings of fest life, such as red carpets, master classes, retrospective programmes, and large crowds attending various screenings. The reality is that gatekeeping happens in the background, and these factors can change a film festival’s programming without ever issuing a dramatic "ban" on that material. The lack of a government exemption certificate, a delayed visa for an international guest, or the appearance of a sudden legal warning against an artist telling their story can create barriers and limit the range of what is shown and discussed at these festivals. Therefore, the total number of acceptable images has not been limited by an outright ban but rather through attrition.

This logic extends beyond festivals. Museums face pressure over exhibitions that touch on religious or national symbols; universities navigate constraints on seminars and film screenings that might attract political scrutiny; publishers weigh legal risk and trolling campaigns when commissioning works on contentious subjects; streaming platforms sometimes remove or quietly withhold content after “informal” objections. In each case, bureaucratic and procedural tools—approvals, funding channels, regulatory guidelines—become instruments of cultural control.

In this landscape, the Battleship Potemkin at the IFFK does not represent rebellion but rather reclassification. A classic of world cinema that had previously been 'settled' as part of the historical record has now become something of a risk, not necessarily because its content has changed. Instead, it is the film's interpretive context that has changed; therefore, the film must be reinterpreted from a new perspective. The question is: What does it mean to screen a film about the 'Revolution' made by a Russian director in an area of the world that is strongly left-leaning, at a time when there is a tendency towards increased centralization and nationalism? The withholding of a waiver has transformed Battleship Potemkin from a historically stable film into an object of contemporary political relevance, at least from a bureaucratic perspective.

The process of controlling access to this film is essential to note because of the procedural nature of the controls. There has been no formal proclamation that Sergei Eisenstein is a 'dangerous' filmmaker, nor has there been any public discussion on why films about Palestinians should not be presented. What remains is extensive documentation that does not appear to have been completed before the date of this policy, numerous files pending completion of 'review,' and advisory notices issued through official channels. Cultural organisers are left to reconcile their uncertainty rather than challenge what has been deemed a formal prohibition. Over time, this encourages self-censorship: programmers anticipate what might cause friction and quietly avoid it, long before any formal refusal arrives.

The Quiet Irony Of Global Acceptance And Local Restriction

The IFFK controversy is marked by a unique irony when viewed alongside the worldwide impact of Battleship Potemkin and other films affected by it. For many years, Battleship Potemkin has been screened at numerous prestigious international film festivals, has had copies preserved in some of the world's most important film archives, and has been taught in many film schools throughout Europe, North America, and Asia. Special commemorative celebrations for the centenary of Battleship Potemkin will take place in 2025, including new restorations of the film, live screenings with a musical score, and essays that explore the film's continued legacy as a significant filmmaking achievement.

In addition, films from Palestine, Africa and Latin America that have been banned from the IFFK have been exhibited at major international film festivals, such as Berlin, Cannes, Venice and similarly significant film events, and have received serious recognition as works of political and artistic merit, rather than as security risks.

Additionally, these films have achieved a degree of academic and archival freedom through the presence of many streaming video platforms on university reading lists and the many streaming video services offered by national and international film museums and collections, as well as public archives. As such, they can be studied and discussed as significant to the understanding of both global cinematic art and the global political context. Internationally, the discussions that arise in the context of these films are often extensive and contentious; however, the movies rarely receive the treatment accorded to objects that require protection from adult citizens.

In India, by contrast, the world’s largest film-producing country appears strangely unsure about how much dissent—or even how much complex history—it is willing to watch in a collective setting. A nation that exports popular cinema on an enormous scale struggles to grant unproblematic space to a century-old silent film and to contemporary works that interrogate power structures at home and abroad. The dissonance is striking: the same films travel in and out of laptops and private hard drives, yet their appearance on an official festival screen becomes a matter of national calibration.

This is not to say that other countries are free of such tensions. Still, the gap between India’s self-image as a confident cultural powerhouse and its procedural anxieties over contested images is increasingly evident. In that gap sits the quiet embarrassment of a festival having to explain to its audience why globally honoured films cannot be shown in a state that has built its reputation on cinematic openness.

The Takeaway

India's film festivals have traditionally provided a "marketspace" where filmmakers, critics, students, and the general public can encounter alternative forms of filmmaking and the histories and political contexts surrounding them, which are usually overlooked by mainstream exhibition practices. IFFK is a film festival that has specifically built a strong reputation as a politically engaged forum, offering opportunities for debate and discussion among its participants.

The events of 2025, however, indicate that festivals may now be viewed as places where negotiation takes precedence over the tradition of an open marketplace. In IFFK's case, curators determine their selections based on potential clearance issues that may arise; state governments decide how much cultural prestige is worth the risks associated with noncompliance; and delegates observe the cancellations of films throughout the festival and realise that simply screening a film involves making a decision that takes place outside the realm of film festivals. Although the spaces are still available for movies to be screened and for discussions to take place, they have devolved into territories where artists, administrators, and politicians must deal with the power relations within these combined spaces.

Therefore, instead of being classified as either completely free or completely controlled performances, festivals should now be recognised as places where artistic intent, administrative authority, and political considerations intersect. Certain films will traverse these newly defined territories with relative ease, while others will face distractions or outright bans on travelling through these venues. The dream of complete autonomy is difficult to sustain when exemption letters can arrive late or not at all, when a classic can be relabelled “sensitive,” and when programmers must anticipate risk as a structural part of their job.

Perhaps the most telling image is not the headline itself, but the scene it implies inside a darkened hall. A silent film from 1925 is scheduled to play. The theatre is packed: students, old festival regulars, filmmakers who discovered cinema through precisely such screenings. The projector stands ready, but the print—or the file—cannot be shown because a clearance has not arrived. The audience waits, unsure whether the screening will happen or be replaced. A century after its first censorship battles, Battleship Potemkin still asks uncomfortable questions, not only about mutiny on a ship, but about who decides what can be seen, and when. The tension between that waiting audience and the unseen permission that may or may not come is where Indian film festivals now seem to live.

2022 © Milestone 101. All Rights Reserved.