STAY CURIOUS

Keep reading to find the excellency out of perfection and skill.

By: Milestone 101 /

2026-01-24

bollywood

One Friday, Two Films: Why Bollywood Treats Overlaps as a Risk

This article examines why Bollywood treats overlapping film releases as high-risk events rather than opportunities. Using the Galwan–Alpha episode and past clashes as reference points, it explores clash anxiety, star power politics, shrinking release windows, and why Hindi cinema still resists Hollywood’s confidence-driven clash model.

Bollywood found itself once more in the midst of a familiar crisis as anxiety, speculation and silent deals were taking place about the two movies’ release clash. Salman Khan's Galwan, which was expected to be an instant classic, was set to be released alongside Yash Raj Films’ Alpha, the first film of a major franchise starring Alia Bhatt and Sharvari. Both films had different target audiences, but both sought to claim the same multiplex screens and customer dollars.

Preparing for an epic box-office clash, cinema operators began calculating potential box-office results; trade publications were preparing to announce the big showdown, and social media was buzzing with early predictions and comparisons. But then, without fanfare or announcement, Alpha shifted its release date to avoid the anticipated box-office catastrophe.

This silent retreat revealed Bollywood's unspoken instinct: despite claims of fragmented audiences and expanding screens, overlaps trigger recoil. Why? The industry faces tighter calendars, fewer prime Fridays, and swelling film slates. What passes as caution masks deeper fears—power imbalances, past flops, and theatrical math where star power trumps theory.

The real question is whether Bollywood will ever learn to stop treating them as disasters — or whether it will continue to blink first, one Friday at a time.

The Industry Mindset: What “Clash Anxiety” Really Means

The prominent explanation from Bollywood for avoiding film clashes is presented in rational, clinical terms rather than in terms of fear of losing audiences. This justification generally stems from the limited number of premium multiplex screens, which generate the vast majority of today's box office revenue. A multiplex must divide its showtimes, screen allocation, and marketing efforts for two or more large films if they are released simultaneously. By dividing resources, a single title's earning potential is compromised to some degree. As a result, all multiplexes prefer to promote a movie with greater potential for a strong opening weekend, based on audience turnout and occupancy maximisation, so that only one film faces the risk of losing traction immediately.

Additionally, filmmakers are now obsessed with opening-weekend results to the point that they not longer view those numbers as early indicators of success. Instead, the initial weekend results have become a "final" decision point on how well a film is performing, and if the film falls short of audience expectations, particularly when compared to another film released during the same week, the perception of that film may harden rapidly before sufficient time has passed to allow for word-of-mouth recommendations to take hold. Additionally, media coverage of these films increases pressure on producers, as the vast majority of articles about these overlapping releases position them as head-to-head competitions, with scorecards to determine winners and losers.

The discourse shifts rapidly from cinema to competition, reducing films to numbers and weekend tallies rather than allowing them to breathe on their own terms. Trade narratives, reinforced over the years by reporting in outlets such as The Times of India and Livemint, have consistently positioned clash avoidance as a form of prudence rather than insecurity, arguing that Hindi cinema operates within tighter margins than Hollywood and lacks the global revenue buffers that allow multiple tentpole releases to coexist comfortably.

Unlike Hollywood, where international markets, genre segmentation, and massive screen counts dilute domestic competition, Bollywood remains heavily dependent on urban centres and premium pricing, making even a marginal dip in early collections disproportionately damaging.

In this sense, conflict anxiety can be characterised more by defensive economic theories than by artistic timidity on the part of studios. Studios do not necessarily fear competition; they are more concerned about the potential loss of control over access to screens, how a film is narratively framed, and how momentum from the opening weekend will carry forward if they lose power. Perception often drives choices in this business; thus, the perceived loss of control may create greater risk for the studio than the actual limits of competition would.

Why Fridays Are Running Out

If avoiding clashes were merely a matter of choosing alternative dates, Bollywood would not find itself trapped in this recurring cycle of postponements and reshuffles. The deeper issue lies in the shrinking number of viable release windows, as the Hindi film calendar has become increasingly congested around a handful of predictable pressure points. Eid, Diwali, Christmas, Independence Day, Republic Day, and extended holiday weekends remain the most coveted slots, offering built-in audience availability and heightened consumption, which makes them disproportionately attractive to stars and studios alike.

Many movies are released at the same time, resulting in bottlenecks. This trend develops well ahead of releases, for example, in July, when movies end up announcing release dates, taking dates off, and announcing them again over and over as producers figure out how to adjust to competing with each other. These problems have been made worse by date blocking, in which major stars and studios hold dates months or even years in advance, even when movies are still being made.

Studios use these dates to secure release windows and to keep competitors out of the same time slots. Bollywood has borrowed this method from Hollywood without the same safety nets used in movies produced at the same scale. The backlog of film caused by the pandemic has also put extreme pressure on the calendar. Movies that COVID-19 delayed, had productions halted or were scheduled to be released after new strategies for theatres, were all looking for space in theatres as the industry sought to regain its earlier level of success. In addition to settling these backlogs, the emergence of pan-India, with South Indian films featuring stars like Allu Arjun, Yash, and Vijay, has captured the same national holidays and audience recognition that Hindi movies had previously dominated.

In this crowded ecosystem, clashes are not always born of ego or brinkmanship. Often, they emerge from logistical inevitability, where moving away from one conflict simply leads a film toward another further down the line. The calendar has become so dense that avoidance is no longer a guarantee of safety; it is only a temporary postponement of confrontation.

When Clashes Hurt: Lessons from Bollywood’s Past

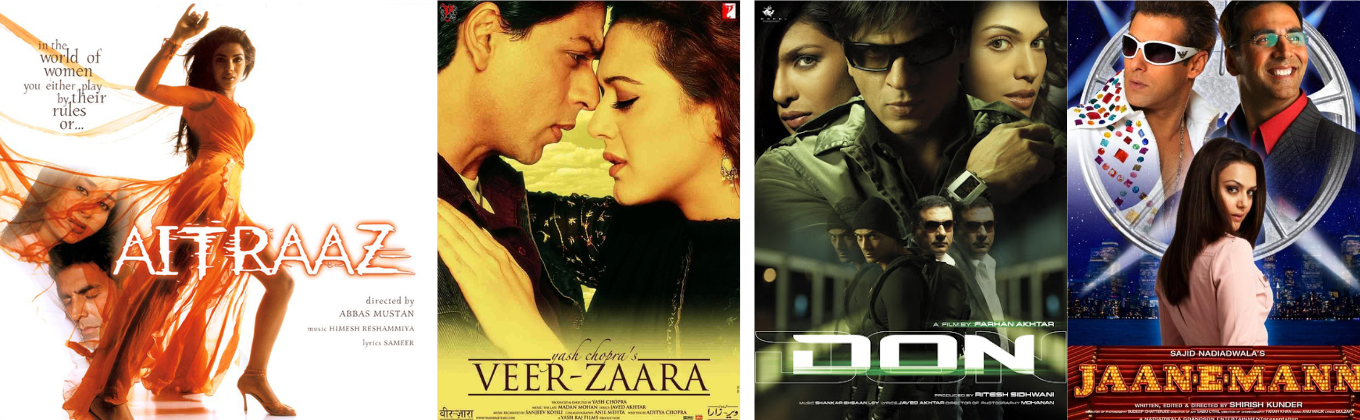

Bollywood's aversion to competing film releases is not the result of theoretical concepts, but of horrible memories of past clashes that caused irreparable damage to the business of filmmaking, the reputations of individual actors, and the relationships among many in the industry. In 2004, it could be shown that the competition between Aitraaz and Veer Zaara illustrates the extreme disparity in these types of confrontations, even though there was no apparent genre difference between the two films.

Aitraaz attempted to capitalise on controversy and contemporary themes to generate interest and attention. At the same time, Veer Zaara, with the added advantage of the peak popularity of Shah Rukh Khan in romantic roles and the emotional format of Yash Chopra, absolutely dominated the box office and the overall cultural narrative at the time of release, thus significantly diminishing any perceived presence (and significance) of the competitor, even though it still performed well financially at the time of release.

A similar type of disparity occurred between Don and Jaan-E-Mann in 2006, where, while Don was able to effectively achieve momentum in terms of storytelling due to its novelty and re-invention of the genre, Jaan-E-Mann was unable to create an identity for itself as a film because of divided audience attention and unfavourable comparisons to Don. In both instances, the impact of these confrontations extended beyond the financial success of each film, shaping perceptions and conversations about them for many years after their theatrical runs.

A frequently cited example of two movies releasing at the same time is the 2008 battle between Ghajini and Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi. However, even in this case, the difference between the two movies was evident. Aamir Khan's physique change to promote Ghajini, along with the marketing campaign surrounding the movie, dominated early discussion, whereas Shah Rukh Khan's film (based on the title) took a more stable approach, relying less on higher grosses than on sustained low ones over time. This illustrates that, while both films survived through their simultaneous release, this does not mean they have equal status.

The clash between Jab Tak Hai Jaan and Son of Sardaar, which took place in 2012, may exemplify Bollywood's fears about crashing films better than anything else can. Both films were assigned release dates and subsequently attempted to enter the marketplace; however, this led to legal problems and personal rancour among those associated with each, making it an industry-wide media event rather than a competitive situation between two films.

While both films generated decent box-office returns for producers, the personal and emotional ramifications of their releases continue to be felt long after the fact. As audiences and critics revisit these two films, they continue to frame their release as a 'clash' rather than a 'celebration' of creative achievement in Bollywood, and this serves as a reminder that even when both films survive as independent and successful releases, at least one will suffer greatly as a result.

Star Power and the Politics of Blinking First

When conflicts arise in the film industry, the determining factor in the collision is much less likely to be based on content or confidence, but instead on who holds the hierarchy. The Bollywood hierarchy establishes that a megastar, or the biggest stars, always maintains their standing as a massive star that cannot be budged. When that happens, distributors and exhibitors align with those stars (take their strategies), as large stars are considered the major players, and all other films typically adjust their positions accordingly. Large studios (which have a large amount of cash and the capability to create long-term franchises) have more power/freedom in deciding to delay releases, absorb disturbances to marketing and maintain brand equity instead of going after competitive opening weekend box office battles, which YRF clearly considered when moving the film Alpha instead of going head to head with Galwan.

Deciding on mid-budget films and emerging franchises is much more difficult. If mid-budget films stand their ground against larger films, they risk being shut out of screens and narratives, and if they move (at an expense), they have an opportunity for undivided attention. The industry's recent behaviour confirms this disparity. The sector has seen films delaying releases (to avoid locations and holiday dates booked by larger films), avoiding films led by Akshay Kumar, avoiding Pushpa 2, or pushing back their schedules because of Yash's growing success as a pan-India star. The South Indian stars now have as much gravitational pull as the biggest stars of Bollywood, and if this is the case, all available space in the film industry is becoming smaller.

The Galwan–Alpha episode reinforces a long-standing truth. Salman Khan did not need to assert dominance explicitly…the ecosystem adjusted around him. In Bollywood, clashes are not resolved through equality or negotiation alone; a sense of invincibility shapes them.

What Stars Say vs What Studios Do

In public statements, Bollywood often espouses harmonious relationships among its stars, who claim that large films should not compete with each other and that the ability of stars to coexist is mutually beneficial to the industry as a whole. Akshay Kumar's view that overlapping (i.e., releasing films with competing release dates) is bad for the film industry is often cited as evidence of the wisdom of the Bollywood business model.

However, the behaviour exhibited among film producers and distribution companies indicates many instances in which film producers aggressively claim their film release weeks without even having a completed script, closely monitor when their competitors announce their films, and negotiate discreetly behind closed doors until one of their films is secure.

Reports from various publications have repeatedly highlighted a contradiction between Bollywood's public statements and its strategies, suggesting that the practice of "defending" one's territory on the calendar is common. In contrast, the sector consistently promotes unity through interviews. The disparity between the two is more due to instincts for survival than to hypocrisy. In Bollywood, perception is everything, and often a method of negotiating through silence works better than confronting a competitor directly.

Does Avoiding Clashes Still Work?

The clash avoidance debate really deserves examination today, when audience habits are so different from what they once were. With the rapid growth of OTT platforms, audiences have learned to consume and engage with multiple stories simultaneously. At the same time, the availability of theatrical releases has decreased drastically as well due to the increase in the number of titles produced each year. Films that have had a 'solo' release but still underperformed indicate that merely controlling their release date will not guarantee success, as clashes can still occur. However, the impact on a film's bottom line isn't severe, suggesting that there is still value in a film's appeal and release position.

While the industry remains fixated on box-office performance in the opening weekend as a means of evaluation/validation, until this obsession changes, the studios will always see any release overlap as a threat to their production/finance processes rather than as an obstacle that can be managed. While avoiding release clashes won't eliminate risks, in an industry that relies heavily on momentum for success, avoidance is often seen as a safer option than defying the perceived regular release pattern.

Why Bollywood Still Resists the Hollywood Model

Hollywood’s comfort with overlapping releases comes from a system designed to absorb competition rather than panic over it. When two big films open on the same weekend, they are rarely fighting for the same audience. The industry benefits from a massive screen base across North America, strong overseas markets, and a viewing culture that trains audiences to sample multiple theatrical experiences in a short span. Just as crucially, Hollywood understands genre segmentation. A superhero film, a musical, and a historical epic are not seen as cannibalising each other by default. They coexist, often deliberately.

Barbenheimer is an example of what we can see today. The contrast between Barbie and Oppenheimer's tone, scale, and the audiences interested in both films created a cultural phenomenon rather than a threat to either film during their shared release date. Instead of splitting audience attendance, both films allowed for more conversation about these two very different films and increased visitation, as viewers took advantage of the opportunity. The competition between these two films was transformed into a promotional event. It did not happen by accident, but rather through the way the audiences and the filmmakers embraced the technology and infrastructure that create these productions.

The pattern of these cultural events has been present in movies for many years. For example, The Dark Knight opened at the same time as Mamma Mia! Both films had opposing themes: a dark, brooding superhero movie and a bright musical featuring ABBA. However, both films had different emotional needs to fill for various audiences and thrived in that manner. Another example of this is Wicked and Gladiator II, which were quickly dubbed “Glicked.” Both films are themed: a fantasy musical and a historical epic. The release dates of these movies did not harm either, as they both offered something different emotionally.

Bollywood, however, operates on thinner margins. Screen counts are limited, weekend dependency is extreme, and star power cuts across genres instead of defining them. A Salman Khan release is not just an action film; it becomes the film of that weekend. Advance date blocking mimics Hollywood’s planning discipline, but without the same safety nets, it becomes defensive rather than strategic. Bollywood borrows the calendar logic, not the ecosystem that makes clashes survivable — which is why resistance remains instinctive rather than outdated.

The Takeaway

Ultimately, the story of Bollywood clashes is not about one movie being “pushed” away by another; rather, it reflects an industry that has learned, through much pain and suffering, that timing may be just as significant as what goes into the actual film itself. The fear among producers of Bollywood films of potentially clashing openings does not stem from a lack of confidence in their product, but rather from the porous economics of theatrical releases. When many films have limited screen counts, narrative gaps exist between them, and audiences view the opening weekend as the final judgment, there is little room for error in predicting how a film will perform.

While it may seem logical and sensible not to clashing with someone else’s opening day for product, Bollywood is not actually avoiding such encounters due to physical embarrassment; however, history has also shown that, regardless of how much a film earns during a regular period, the wounds will continue living on through the residual effect of lower box office during the same period and diminished audience support for both films; therefore, under these conditions, rational rationale would be to urge extreme caution.

Yet as calendars grow tighter and pan-India releases compete for the same weekends, clashes will become less of an exception and more of a reality. The real question is whether Bollywood will ever learn to stop treating them as disasters — or whether it will continue to blink first, one Friday at a time.

2022 © Milestone 101. All Rights Reserved.