STAY CURIOUS

Keep reading to find the excellency out of perfection and skill.

By: Milestone 101 /

2025-12-24

hollywood

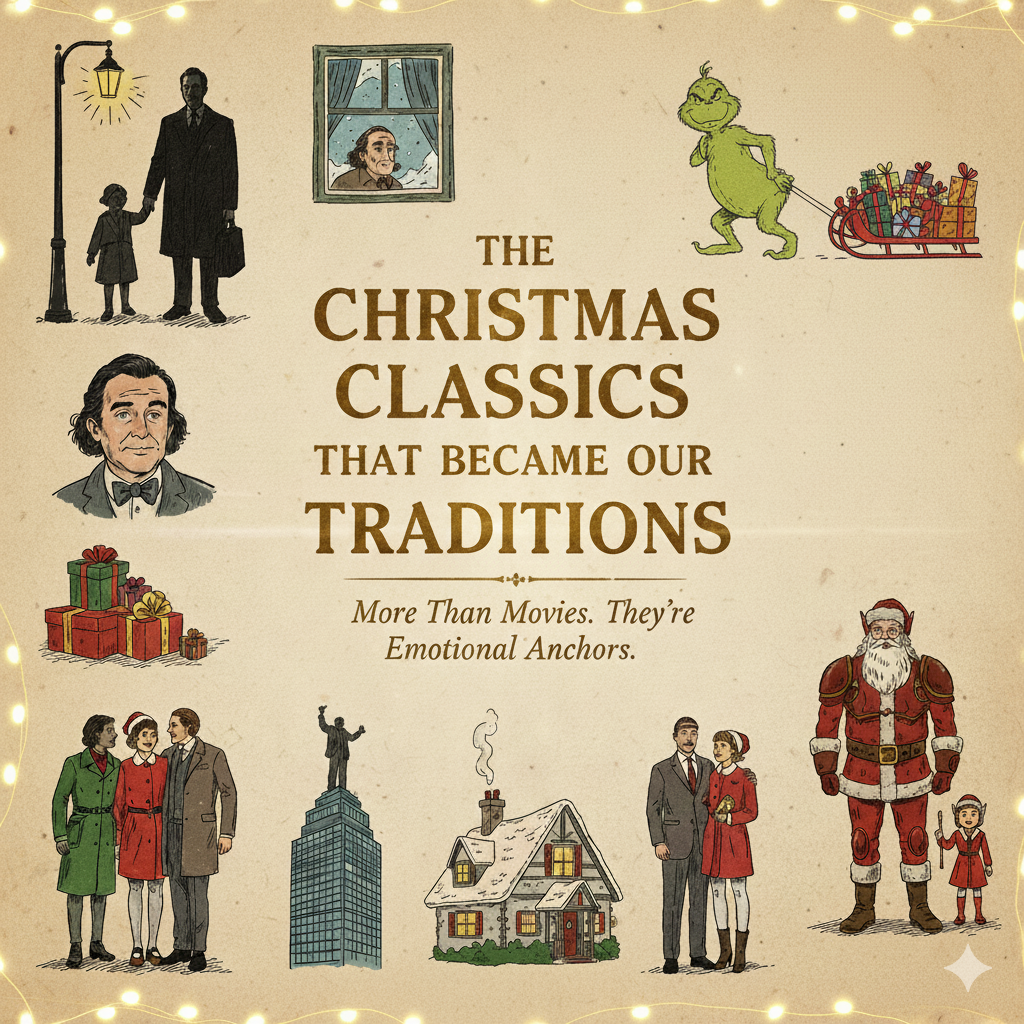

The Best Christmas Classic Movies That Turned Into Traditions

A reflective listicle on Christmas films that evolved into yearly rituals. From classics to modern entries, the article explores why certain movies return every December, not for cheer alone, but for the emotional recognition they offer across different stages of life.

Christmas movies are rarely chosen the way other films are. They aren’t discovered through algorithms or glowing recommendations. They arrive quietly. One year, you watch them because someone else puts them on. A parent. A sibling. A partner. Then, without realising when it happened, they become yours.

They start playing while the house is half-lit and half-messy. While food is cooking. At the same time, someone is irritated about something small. You don’t always sit down to watch properly. But the film stays on. And somehow, it stays with you.

Scroll through Rotten Tomatoes’ recurring Christmas lists or IMDb’s long-standing holiday rankings, and the same titles appear year after year. Netflix has repeatedly noted that December viewing habits lean towards repetition rather than novelty. At Christmas, people don’t want a surprise. They want recognition, familiar faces, predictable endings, and emotional safety.

What’s interesting is that many of these films are not relentlessly joyful. Some are heavy. Some are strange. Some are outright sad for long stretches. And yet, they endure. That’s because Christmas movies don’t last by being perfect. They last by returning us to specific emotions. Comfort. Loneliness. Mischief. Regret. Family chaos. Second chances. These films don’t change much from year to year. We do. That’s why we keep coming back.

This listicle curates the Christmas films that have become traditions, not because they demand attention, but because they invite it. They sit with us through different phases of life and mean something new every time.

1. It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) - The Moral Spine of Christmas Cinema

Few Christmas films are as routinely misunderstood as It’s a Wonderful Life. It’s often remembered as sentimental, uplifting, and life-affirming. In reality, most of the film is bleak.

George Bailey is tired. Financially trapped. Emotionally worn down. His dreams have been postponed so often that he barely remembers what they were. The world does not reward his kindness in any obvious way. By the time Christmas arrives, he is not grateful. He is desperate, and that honesty is why the film refuses to age out.

Unlike modern holiday films that rush towards comfort, It’s a Wonderful Life lingers in discomfort. Christmas doesn’t magically solve George’s problems. It forces him to confront them. His loneliness is not exaggerated for drama. It’s ordinary. Domestic. Familiar.

Town & Country often describes true classics as emotional anchors rather than historical artefacts. This film fits that idea perfectly. It doesn’t matter how many times you’ve seen it. The weight still lands, especially as you grow older.

As children, viewers often focus on Clarence and the fantasy structure. As adults, the film becomes about compromise, burnout, and quiet resentment. About being beneficial to everyone except yourself. Each rewatch shifts the emotional centre.

That’s why it returns every December. Not because it comforts immediately, but because it understands the season’s emotional pressure. It admits that generosity can feel exhausting. That goodness can feel invisible. And then, without denying any of that, it offers grace.

2. A Christmas Carol (1951) - Redemption Without Soft Edges

If It’s a Wonderful Life is about the cost of kindness, A Christmas Carol is about the cost of avoidance.

The 1951 adaptation remains one of the most enduring because it refuses to turn Scrooge into a cartoon villain. His cruelty is rooted in fear. Fear of loss. Fear of dependence. Fear of emotional exposure.

What makes this version last is its moral seriousness. Christmas does not redeem Scrooge because it’s Christmas. He earns his redemption by witnessing the emotional damage he has caused by confronting a future shaped entirely by isolation.

The film doesn’t rush this reckoning. It sits with regret. With the idea that emotional withdrawal is a choice, even when it feels like self-protection. That’s why this story keeps returning in so many forms. Not because audiences need reminding to be kind, but because they need reminding that isolation hardens quietly. Christmas becomes the moment when that hardening is interrupted.

In a season obsessed with cheer, A Christmas Carol survives by insisting on reflection first. That refusal to soften its message is precisely what makes it comforting. It doesn’t lie.

3. Home Alone 1, 2 & 3 (1990-1997) - Chaos, Childhood, and the Comedy of Survival

On the surface, Home Alone presents itself as a broad slapstick fantasy, where a child turns domestic objects into weapons and pain becomes comedy. Yet its endurance as a Christmas tradition comes from something far more intimate. Kevin McCallister is not abandoned out of cruelty, but out of chaos. His family is loud, distracted, overwhelmed by travel and logistics, and emotionally stretched thin. The film refuses to paint them as villains, which is precisely why the situation feels real. It captures how easily care can slip through the cracks during moments meant to celebrate togetherness.

At its core, Home Alone is powered by abandonment anxiety. Kevin’s sudden independence is exhilarating because it masks vulnerability. His competence feels empowering, but the film never pretends that self-sufficiency is enough. Beneath every elaborate trap is the same emotional need: to be noticed, to be missed, to be wanted. That emotional clarity is why the film continues to dominate IMDb and Rotten Tomatoes holiday lists despite its implausibilities. It reflects the emotional texture of Christmas itself, loud and loving, chaotic and unintentionally hurtful, all at once.

Home Alone 2: Lost in New York understands that it cannot recreate the emotional purity of the original, so it chooses escalation instead. New York becomes a fantasy space, turning Kevin’s isolation into temporary liberation. The traps grow bigger, the setting more theatrical, and the loneliness less central. What keeps the sequel in rotation is familiarity. The beats repeat with variation, allowing viewers to anticipate moments they already love. That predictability becomes comforting, transforming spectacle into ritual.

Home Alone 3 rarely earns affection on artistic merit alone. Without Kevin, the emotional core is thinner, and the charm more diluted. Yet it persists in holiday line-ups because franchises build tradition through repetition rather than perfection. Watching the weaker instalment becomes part of the ritual itself. It marks time, evokes earlier viewings, and reconnects audiences with past versions of themselves. Christmas viewing, after all, is less about quality control and more about continuity. Home Alone 3 survives because it belongs to a shared seasonal memory that extends beyond any single film.

4. Elf (2003) - Innocence as Rebellion

Elf works because it refuses cynicism at a time when cynicism often feels like maturity. Buddy is not naïve because he fails to understand the world around him. He understands it well enough to reject its emotional restrictions. His enthusiasm is deliberate—a choice rather than a flaw. In a culture that rewards detachment and efficiency, Buddy’s openness feels quietly radical. He insists on sincerity in spaces that have forgotten how to make room for it.

The film recognises how strange adult behaviour appears through unguarded eyes. Office politics, emotional restraint, and transactional kindness appear absurd when contrasted with Buddy’s directness. Significantly, the humour never punches down. The adults around Buddy aren’t villains or bullies. They are exhausted and worn down by routine, expectation, and disappointment. Elf treats that fatigue with surprising empathy, allowing laughter without cruelty.

That distinction is why the film continues to work across generations. Children respond to Buddy’s physical comedy and oversized reactions. Adults, meanwhile, recognise the slow erosion of wonder that the film quietly critiques. They see the world that dulled Buddy and, in moments, perhaps recognise themselves in it.

Slapstick in Elf is not merely a comedic tool. It becomes a form of resistance. The film insists that joy can be chosen without being ignorant of reality. That belief returns every December because it offers hope without instruction. It doesn’t lecture. It simply shows what openness might look like if we allowed it back in.

5. How the Grinch Stole Christmas (2000) - Soft Rebellion

How the Grinch Stole Christmas endures because it understands that rejection is often a form of self-protection. The Grinch is not a villain in the traditional sense. He is a refusal. A figure who has stepped away from a version of Christmas that feels loud, crowded, and emotionally overwhelming. His isolation is not driven by cruelty, but by exclusion. He exists on the margins, watching a celebration that seems designed for those already inside it.

His bitterness grows from distance rather than malice. He doesn’t hate joy itself. He resents how joy is performed, measured, and enforced. The Who’s version of Christmas is relentless in its noise and certainty, leaving no space for quiet, doubt, or difference. The Grinch’s withdrawal becomes an act of emotional survival, not moral failure.

That framing is why the film lasts. Crucially, the Grinch does not learn to participate in Christmas by consuming it better. Instead, Christmas reshapes itself around him. When spectacle falls away, what remains is connection. Noise gives way to listening. Excess gives way to presence.

Animation allows this emotional shift to feel gentle rather than heavy. Loneliness becomes visible through posture, colour, and framing. Alienation is softened into something recognisable rather than shameful. The film endures because it validates emotional distance before resolving it. It doesn’t punish withdrawal. It understands it, and only then offers a way back.

6. Klaus (2019) - Animated Loneliness and Melancholy Wrapped in Warmth

Klaus is one of the quietest modern Christmas films to become a repeat watch, and its restraint is precisely what gives it lasting power. The world it introduces is cold, isolated, and emotionally stripped bare. Acts of kindness are not instinctive here. They have to be learned, often clumsily and without immediate reward. The film resists the urge to rush toward warmth, allowing silence and stillness to shape its emotional landscape.

Netflix has often pointed out that animated holiday films bridge age gaps because they allow sincerity without irony, and Klaus embodies that philosophy completely. It never winks at the audience. It trusts its emotions. The film is gentle without becoming saccharine, and melancholy without tipping into despair. Its sadness feels honest rather than heavy, grounded in emotional absence rather than dramatic tragedy.

What the film understands deeply is that many people approach Christmas not from abundance, but from lack. From fractured communities, emotional distance, or quiet loneliness. Friendship in the film forms slowly, almost reluctantly. Generosity is not assumed as a default virtue. It is taught, repeated, and earned through small actions.

The film feels like a blanket because it respects silence. It allows pauses to breathe and emotions to settle. That respect creates comfort without noise. Viewers return year after year not for spectacle, but for the calm assurance that warmth, when it arrives, is deserved.

7. Die Hard (1988) - Ritual Through Argument

Whether Die Hard is a Christmas movie matters far less than the fact that people feel compelled to argue about it every single year. That argument has become part of the ritual itself. Rewatching the film is no longer just about the story on screen, but about participating in a familiar cultural disagreement that resurfaces with the season. For many viewers, pressing play on *Die Hard* is a way of acknowledging Christmas while pushing back against its expected emotional softness.

The film offers a version of the holiday stripped of comfort. There are no warm gatherings or gentle reconciliations. Instead, there is tension, isolation, and survival under pressure. Christmas exists not as a mood, but as a setting that heightens stress rather than easing it. That inversion is precisely what draws audiences back. It reflects a reality many recognise but rarely see represented in holiday cinema.

Online debates, video essays, and annual defences keep *Die Hard* alive beyond the screen. Each rewatch is reinforced by conversation, disagreement, and humour. Repetition combined with debate sustains relevance.

Die Hard, without a doubt, is a Christmas tale because it acknowledges that the holiday is not universally gentle. For some, it is exhausting, emotionally loaded, or outright hostile. The film doesn’t soften that truth. It embraces it. And in doing so, it earns its place in the seasonal canon.

8. The Holiday (2006) - Romantic Escape and Emotional Distance

The Holiday is built on a fantasy that feels especially powerful in December: the idea that changing your surroundings might allow you to change yourself. A different house. A different country. A different rhythm of life. The film leans into this desire without mocking it, understanding how appealing reinvention feels as the year comes to an end and emotional expectations are at their highest.

Christmas intensifies longing rather than dissolving it. The season encourages reflection, comparison, and quiet self-assessment. The Holiday recognises that unresolved feelings do not pause for festivities. They often surface more sharply. The film’s characters carry heartbreak, disappointment, and self-doubt with them across borders, discovering that distance can offer clarity but not instant relief.

What makes the romance work is its hesitation. Love does not arrive fully formed or confidently declared. The characters are cautious, shaped by past wounds and reluctant to trust their own optimism. That guarded hope feels more truthful than grand romantic gestures. It allows vulnerability to unfold gradually, without pressure.

The film returns year after year because it captures emotional transition rather than emotional resolution. It sits in the in-between space where healing hasn’t yet happened, but feels possible. That suspended moment resonates deeply during Christmas, when endings and beginnings blur, and change feels both frightening and necessary.

9. Love Actually (2003) - Emotional Messiness as Comfort

Love Actually has aged unevenly, and most viewers are fully aware of it. Some storylines now feel dated. Others provoke discomfort rather than warmth. Yet despite growing critique, the film continues to return every December, occupying the same space in holiday line-ups year after year. Its endurance suggests that relevance and perfection are not the same thing.

The film’s lasting strength lies in its refusal to present love as a single, coherent experience. Instead, it splinters love into multiple forms. Romantic, familial, unrequited, awkward, selfish, generous, fleeting. Often all at once. By doing so, it resists the pressure to idealise connection, especially during a season that demands emotional clarity.

Christmas heightens vulnerability. It brings expectations of closeness that many people struggle to meet. Love Actually captures that emotional exposure without insisting on neat conclusions. Some characters find resolution. Others remain suspended in longing or disappointment. That imbalance feels true to life, particularly during the holidays.

IMDb continues to list the film because recognition outweighs criticism. Viewers return not to celebrate its flaws, but to see their own emotional contradictions reflected in it. The comfort comes not from perfection, but from honesty as the film allows its audience to witness its emotional chaos and exist without apology.

10. Red One (2024) - Inside Santa’s Operation: Myth, Muscle, and Modern Spectacle

Red One approaches Christmas from an angle most holiday films avoid. Instead of focusing on belief or sentiment, it treats Santa Claus as an institution. A global operation that requires logistics, security, surveillance, and protection. This shift is what makes the film interesting, even if its place as a future tradition remains undecided.

Santa here isn’t just a symbol. He’s a working figure at the centre of a vast system, supported by elite protectors who function like a mythological security detail. The North Pole becomes less a magical wonderland and more a high-tech command centre. Elves aren’t just helpers. They’re specialists. Guardians. Problem-solvers. Christmas, in this world, doesn’t happen by goodwill alone. It’s managed, defended, and maintained.

That framing reflects a modern impulse. Audiences today are curious about process. About how things work behind the scenes. Red One taps into that curiosity by reimagining Christmas as an operation under threat, where belief must be protected as fiercely as any physical asset.

Whether this vision becomes tradition depends on time. Older classics earned their place through repetition, not spectacle. Red One plants the groundwork. If viewers return to it year after year, its mythology may deepen. Tradition, after all, isn’t declared. It’s accumulated.

The Takeaway

Christmas movies endure because they make space for contradiction. They allow joy and sadness to exist together. They normalise family dysfunction instead of pretending it disappears under fairy lights. They permit humour without denying pain, and comfort without demanding emotional perfection. These films don’t change. We do.

Each December, we return to them not to escape ourselves, but to quietly measure ourselves against them. A scene that once felt funny might now feel tender. A moment that once felt slow might suddenly feel heavy—lines we barely noticed before begin to linger. The films stay fixed, but our relationship with them shifts, shaped by age, experience, loss, and growth.

That’s why rewatching becomes a ritual. These movies act like emotional markers, helping us locate where we are in our own lives. They remind us of who we were when we first saw them and who we’ve become since. Watching them alone feels different from watching them with family. Watching them as a child feels different from watching them as a parent, or as someone missing home.

They last not because they capture Christmas perfectly, but because they understand its emotional contradictions. They accept that the season can be generous and lonely, joyful and exhausting, hopeful and heavy, often all at once. And in allowing that complexity to exist without judgment, these films permit us to change inside them. That, quietly and persistently, is how tradition forms.

2022 © Milestone 101. All Rights Reserved.