STAY CURIOUS

Keep reading to find the excellency out of perfection and skill.

By: Milestone 101 /

2025-07-29

bollywood

The Politics of Film Certification: How and when did Censor become a Banning Tool?

This article explores how India's film certification board, CBFC, often acts as a censoring body rather than a classifier. It discusses political overreach, moral policing, and the self-censorship filmmakers resort to, ultimately questioning whether certification still protects artistic freedom or simply enforces ideological control.

If you have watched James Gunn's 'Superman' in the theatres, you would have noticed abrupt cuts in some scenes, and you weren't wrong. The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) cut 30 seconds of kissing scenes between Superman & Lois Lane in the climax. Take the failed invasion, for instance, where the Green Lantern uses the middle finger to dismantle the enemy army tanks. Indian audiences didn't get to see these scenes as the censor board used their proverbial scissors to remind us citizens of our sanskaars. Yup, it's down to this!

Indian cinema is always a reflection of the moral, political, and cultural currents of its time. However, it is seldom that making a film reach its audience is an empirical artistic process that does not involve navigating a minefield of committees, laws, inspections, and unwritten rules. The CBFC (the Censor Board) has sought to know itself not just as a proscriptive or prescriptive body, but as a moral and political gatekeeper. Taking its inspiration from the Cinematograph Act of 1952, which purports to provide guidelines on "certification," it extends beyond that to censorship, bans, and even the outright erasure of culture. Films are not only censored by people like the CBFC and others, but people self-censor for fear of being faced with a backlash, or worse, a ban. This is a testament to the chilling effect that the CBFC has on art and therefore represents an even greater level of scrutiny than films commissioned by the CBFC.

Despite the adult audience from all backgrounds wanting more sophisticated stories and more challenging viewpoints already reflected in contemporary Indian cinema, the Board considers society to be perpetually juvenile and needs to protect them from trauma. Creative politics of film certification - combined with the abolishing of other means of critical appellate mechanisms, such as the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) in 2021, can provide clarity not only about the way the CBFC functions, but also that its activities are less about certifying and all about controlling - controlling narratives, managing ideas and maintaining the right to offend and subvert.

This article examines the CBFC’s role as a moral authority. It reflects on the political censorship or delays of films, as well as the self-censorship that filmmakers exercise to avoid controversy or bans, which has helped to lessen adult themes despite changing levels of maturity among viewers.

What is the Indian Central Board of Film Certification?

The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) was established under the Cinematograph Act, 1952. It is a statutory body of the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting in the government of India. Its primary role is certifying films for public screening in India. CBFC certifies films in four categories: U (unrestricted), A (restricted to adult audiences), UA (parental guidance for children under 12), and S (specialist audiences or ‘restricted’). The CBFC is located in Mumbai, has a chairperson, up to 25 members and works with nine regional offices and advisory panels appointed from the local film industry, otherwise known as the local advisory panel (LAP), mostly consisting of local directors, actors, producers, etc.

When it was first established, the CBFC's role was to classify films and determine their suitability for various segments of the audience. However, CBFC became synonymous with state-mandated film censorship. All Indian and foreign films must receive clearances from the CBFC before any exhibition of the film or distribution can take place anywhere in India. The CBFC does not have direct enforcement mechanisms. Still, most filmmakers realise that if they do not comply with the CBFC's actions and directives, they will never be able to exhibit the film in India legally. The powers of the CBFC are so extensive that compliance often requires filmmakers to make changes or edits to their films to avoid violating terms, with justifications based on claims of "public order", "morality", or "decency". This places the CBFC in the position of deciding for Indian society and the film industry what is an acceptable film to watch or discuss. The elimination of the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT) in 2021 removed an essential and accessible appeals process. Without FCAT, filmmakers seeking to appeal CBFC decisions must embark on lengthy court battles to have their films screened despite the CBFC decision.

How the CBFC Has Cut Scenes from Bollywood Films

The institutional censorship of the CBFC is not only a historical record, but the CBFC's short history is littered with instances where political, religious, and moral pressures have skewed the arc of cinematic storytelling.

Ore Oru Gramathiley (1987)

The CBFC banned this Tamil film for criticising government policy in its portrayal of caste-based reservations. This occurred very quickly after the film's release. Only after a Supreme Court intervention said that it was inappropriately banned, did the CBFC clear the film as revealing how bans are blunt instruments of repressive control over dissenting opinion on constitutionally protected subjects (like affirmative action).

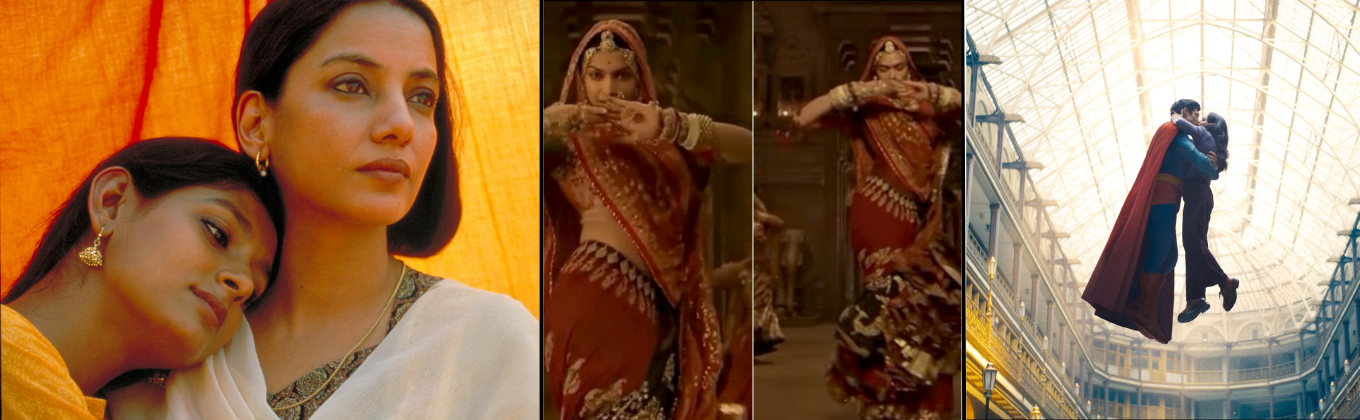

Fire (1996)

Deepa Mehta's film pioneered Indian cinema with its openly presented lesbian relationship between two sisters-in-law. It was even allowed by the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) to be released in May 1998 with an "A" (Adults Only) certificate, requesting only a minor change (the character name of "Sita" was changed to "Nita", so as not to create religious controversy). Although "Fire" was permitted to be released in Indian cinemas, the official and state-sanctioned approval was met with significant protests from right-wing groups that attacked cinemas and demanded, in unison, that the film be banned and labelled the film "immoral” and “un-Indian." Therefore, theatre owners succumbed to this pressure and withdrew “Fire” in many cities, becoming a visible example of how state-sanctioned certification does not guarantee protection from extra-legal censorship when politics and morality converge.

Vishwaroopam (2013)

Kamal Haasan's Vishwaroopam and its sequel were edited multiple times: scenes or terms related to “Pakistan”, “Allah” and “Bharat Mata” were muted, bedroom scenes were halved, and blood/gore was also reduced after pressure from religious organisations. The CBFC was interested in avoiding political controversy as much as it was in classifying the content.

Udta Punjab (2016)

The Board mandated 94 cuts to Udta Punjab, including the removal of key narrative elements — city names, references to Punjab, and crucial narrative context. The stated reason was coarse language and drug use, but at the intrinsic level, the motivation was clear: the Board wanted to avoid political embarrassment. By removing those particular locatives, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) completely removed the film's CHUNNI-- a raw and honest representation of Punjab's drug crisis and the complicity surrounding it. The CBFC left audiences with the probably-hardest-to-watch 'fiesta' of what was initially intended to be a feature-length social critique. This suggests that censorship isn't just about content, but rather an analysis of the political image versus the truth.

Lipstick Under My Burkha (2016)

The film was initially rated unfit for public screening due to it being "lady-oriented," as well as containing "sexual scenes, abusive words, and audio pornography". The more the CBFC objected to the rating, the more it reflected an unease around the notion of women's desire and autonomy than just procedural objections. The film appealed and was eventually awarded an A rating by the appeals board, but only after several cuts. It demonstrated how the board categorised women's stories and rated them more harshly, oftentimes, when women spoke about sex on their own terms.

Padmaavat (2018)

Sanjay Leela Bhansali's magnum opus received certification from the CBFC only after making multiple compromises, including retitling the film from ‘Padmavati’ and adding disclaimers to indicate its fictitious nature, altering the "Ghoomar" song, and cutting various scenes. Despite being cleared by the board, the film was attacked or disrupted in multiple states for allegedly presenting a distorted historical account of an Indian controversy. If anything, the controversy highlighted how little CBFC approval means when there are politically or even fringe outbursts. Certification is no protection when sentimentality refuses to acknowledge legality, and filmmakers are left to fend for themselves.

Punjab '95 (2025)

Based on the life of human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra, the planned Punjab ’95 ran into 127 CBFC cuts - removing Khalra's name, references to the Punjab Police, Sikh prayer hymns, and even "Punjab" in the title. Although it was set to premiere at TIFF in 2023, Indian authorities pressured it to be pulled from circulation. As of the time of this writing (July 2025), it has still not been released in India, effectively erasing an uncomfortable history through bureaucratic processes.

Stolen (2025)

Directed by Karan Tejpal, the film focuses on the chilling subjects of child abduction and mistaken identity. Before it even received a certificate, the film found itself in a dispute with the CBFC over multiple cuts. These cuts were not just cuts; they were cuts that delayed its release and undermined the narrative’s social value and emotional impact. The board’s unease with the frank portrayal of the failure of our systems and the damaging ramifications of trauma for individuals suggested a larger pattern: films that make social evils real are often resisted. Stolen became one more instance of realism, which was treated as a danger rather than a prompt for serious contemplation.

L2: Empuraan (2025)

Mohanlal's film drew criticism for portraying, among other tragedies, the 2002 Gujarat riots. The production faced accusations of pushing an "anti-national agenda" and was cut by as few as 17 to as many as 24 cuts required by the CBFC. The filmmakers had to tone down or remove almost all valuable riot-related sequences and also sections of violence against women. The producers had to capitulate to a barrage of political pressures, renaming the antagonists and softening the content that they could not edit out. They, in effect, muffled the film's critique and watched as it was shaped into something entirely different from what was intended—from a hard-edged, political film to a softer, palatable film for audiences, thereby illustrating how clumsily the CBFC collects ideology (as if to protect artists) versus offering an honest account of history.

Janaki V vs State of Kerala (2025)

The film under review incurred 96 edits requested by the CBFC after submission. The primary objection was the name of the protagonist, "Janaki," which the board found objectionable because it is the name of the Goddess Sita. The objecting CBFC board members' only assumption was that a flawed or complicated character could not possibly share a name with a goddess. After many legal conversations, the number of cuts was reduced—the only audio mutings were two examples, and the title changed. The film allowed people to see how often the CBFC invokes religious sensitivities in their mandates, limiting and controlling how stories can be told. How the CBFC imposes its moral dictates determines the spatial and aesthetic context in which characters—and women most critically—can be represented in Indian film.

Santosh (2024)

Despite receiving international acclaim, the UK-produced Santosh was denied a theatrical release in India after the CBFC raised objections over its portrayal of police brutality, caste discrimination, and misogyny. The board demanded cuts that the filmmakers deemed “unacceptable,” leading them to choose an OTT release instead. This move highlighted a growing pattern—where films that challenge social hierarchies or expose systemic violence face disproportionate scrutiny. The CBFC’s ideological discomfort with such themes shapes what Indian audiences are allowed to see, revealing how censorship is used not just to “protect” viewers, but to preserve uncomfortable silences around power and inequality.

Phule (2025)

Phule, a biopic on social reformers Jyotirao and Savitribai Phule, encountered unwarranted obstacles from the CBFC before its release. Although firmly grounded in well-known history, the board insisted on various cuts, as it was concerned about available “sensitive” material that showed caste realities too well. Of course, it wanted to remove the explicit mention of critical historical terms, such as “Mahar” and “Mang,” from the biopic about Jyotirao and Savitribai Phule, particularly regarding caste discourse. But it went as far as demanding to censor even a simple voiceover explanation about caste, removing critical context from a film that was neither sensationalist nor incendiary.

This raised significant questions—how could something based on truth be too controversial to see? The interference delayed the release and caused the filmmakers to dilute their message, thereby lessening the intended impact of the story. Phule is not just a film— it is India’s struggle against caste and patriarchy. Rather than promote it, the CBFC appeared to try to drown it out.

Dhadak 2 (2025)

The film, which has a release date of August 1, has undergone 16 edits by CBFC regulations. Of course, these edits also serve to soften the thrust of social critique in the film. They included the muting of caste slurs like 'chamar' and 'bhangi,' the removal of a verse by Tulsidas, and the deletion of a scene featuring a blue-painted dog, which was likely flagged as potentially denoting caste in some way. Interestingly, the disclaimer was stretched to nearly two minutes, with a disclaimer on a disclaimer, and there was an incredible amount of irrelevant explanations. This demonstrates, beyond mere sensitivity, a failure to address head-on the realities of caste, as well as the danger of settling for soothing over realism in films that attempt to convey uncomfortable realities.

Kabir Singh (2019) and Animal (2023)

With irony, hyper-violent/ misogynistic films like Kabir Singh and Animal have somehow managed certification with limited restrictions, sparking widespread conversations for their glorification of hyper-violence, toxic masculinity and problematic representations. While both offered some of the most concerning representations regarding gender, the CBFC passed both with minimal cuts or restrictions. This anomaly presents us with a stark dilemma: when the board rigorously censors a film for exploring political commentary, challenges historical realism, or introduces progressive ideas to the public, what are we to make of the CBFC passing almost carte blanche regressive narratives?

The answer can be identified as the inconsistency in the CBFC's priorities. Commercially viable films that demonstrate some commercial optimism are often granted almost unfettered access to certification, regardless of how disgusting their content is. At the same time, socially conscious cinema is closely examined and censored for its "boldness" or "alleged sensitivity."

Operating politically in anyone's interest other than the market creates room for disinterest. If controlled, profit-driven, hypermasculine fictions face fewer hurdles than those challenging the status quo of inequality. We are not witnessing fair certification; we are seeing censorship articulated through market politics.

How the CBFC Has Cut Scenes from Hollywood Films

India’s censorship process affects not only domestic films and the industry, but also international narratives, many of which are routinely neutered or made to disappear before being seen by too many people in India.

The Fabelmans (2022)

Steven Spielberg's 'The Fabelmans' is a profoundly personal examination of his childhood; it also had several anti-Semitic slurs muted by the CBFC. The irony was palpable—muted slurs intended to highlight real-world hate and bullying resulted in diminishing the emotional and societal ugliness of the film as a whole. Rather than trusting audiences with the context, the board suppressed reality for the goal of "palatability", undermining the very message of prejudice and resilience the feature sought to offer.

Oppenheimer (2023)

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, for instance, underwent digital censorship, including a “CGI black dress” that covered nudity, digitally removing cigarette smoke from scenes, and a sex scene that quoted the Bhagavad Gita; this scene incited outrage from authorities and nationalist groups. The Minister for Information and Broadcasting publicly questioned how this scene was allowed to pass the certification process, and an additional round of “hurt sentiments” was reignited.

Babygirl (2024)

Halina Rein's Babygirl, starring Nicole Kidman, received an "A" certificate from the CBFC, which is supposed to allow it to be shown uncut to a paying adult audience. However, the editor determined that over three minutes of erotic imagery and what the board considered "salty language" had to be cut. The absurdity wasn't lost on anyone, as critics pointed out the ridiculousness of certifying it in an "A" category for adult audiences, yet censoring it as if the viewers were underage. This raises a familiar question: if a category like "A" exists to denote "suitable," why do we bother with a designation if every adult film is treated as if it must be appropriate for children?

The Brutalist (2024)

Brady Corbet's "The Brutalist", a stark examination of art, war, and exile, suffered cuts by the CBFC - just over a minute of nudity and sexual content was cut before its release in India. The scenes may not have occupied a lot of time in the film, but their absence diminished the film's emotional cadence. Guy Pearce, the film's star, pointed out that "the uncomfortable parts help the story land," emphasising that seemingly minor cuts can often diminish the real purpose of adult storytelling. Once again, being uncomfortable with complexity and intimacy resulted in the CBFC releasing a diluted version of a film that deserved to be seen in its entirety.

Anora (2024)

Brady Corbet's "The Brutalist", a stark meditation on art, war, and exile, was cut by the CBFC - and lost in the cutting room - just over a minute of nudity and sexual content was excised before it was made available in India. While it does not appear that those cuts contained much screen time, losing them altered the film's emotional cadence. Guy Pearce, one of the film's stars, stated, "The uncomfortable moments help the story land," and reminded us how minor cuts sometimes minimise the effect of adult storytelling. Being uncomfortable with complexity and intimacy meant that the CBFC once again released a diluted version of a film that had earned the right to be seen in its entirety.

The Apprentice (2024)

The Apprentice, a biographical film about Donald Trump's formative years, was subject to heavy cuts for its Indian release. Scenes of nudity were cut entirely, a scene depicting a sexual assault was edited down 75% from what was shown before, and they even cut words such as "Negro," which historically has been a legitimate term to use. The cherry on top was the studio inserting warnings regarding smoking and drinking, which further interrupted the film's visual flow. Abbasi denounced this arm disfigurement of his artistry by saying the world appears to require "a vaccine against censorship." His exasperation was warranted—the Indian version of The Apprentice was far removed from any semblance of the original, which begs the age-old questions of 'what, exactly, are we capable of emoting?'

Monkey Man (2024)

The CBFC accepted Dev Patel's politically charged action-thriller Monkey Man. It was denied due to bureaucratic indecision, with neither a certificate, nor a justification, nor a response from the board. The CBFC demonstrated that it did not need to stomp down on the film—instead of saying, no, it can't be shown, they could just stall. So this was not the kind of censorship we commonly recognise, in that they did not impose any outright ban against the film. They employed procedural stalling as a form of passive resistance. Monkey Man was not too violent, latent or too explicit—it was too pointed. Instead of exposing its questionable practices of censorship, the Board has opted for plausible deniability and nondisclosure policies and practices over clarity and authenticity.

Superman (2025)

In a series of smaller but telling moves, a 33-second kiss between Superman and Lois Lane was deemed “overly sensual”, along with a battle scene where a character throws off an army tank with a giant middle finger, which were cut from the film, drawing attention to the double standards applied to Hollywood versus Bollywood content in India.

F1: The Movie (2025)

In F1: The Movie (2025), this presumably minor moment triggered a tiny, yet meaningful, change. A middle-finger emoji, commonly seen in texting vignettes, was replaced with a closed fist – apparently changing a frustrated gesture into a less offensive one. In theory, it's a small change. However, it is a good indication of the micro-censorship the CBFC employs to force censorship, even in the most minor details. These changes are not about public morality, but more about disinfecting the messy and imperfect edges of life. As films go through this sanitising, they can become stylised, inauthentic, and strangely machine-like, as though genuine emotion or expression must be watered down or restricted, even when representing the real world, so that they do not create a backlash.

Thunderbolts (2025)

Marvel’s Thunderbolts, a motion picture marketed towards older teens and young adults, had five mild expletives expunged for its Indian release. They weren't harsh curses, just the sort of language adolescents use regularly. However, the fact that the CBFC edited these reflects its enduring discomfort with even the softest indication of adolescent realism. The edits didn't affect the plot; however, they did alter the tone, which made the film feel slightly out of touch with its intended demographic. Sanitisation trumps authenticity; even superhero movies lose authenticity. The Board's approach feels less focused on framing permissively and more on acting like messiness doesn't exist.

The Long and Baffling History of CBFC’s Edits

The CBFC has taken a harsher stance on censorship, which has later taken on a curveball of ridiculousness and inconsistency. The story of India's post-independence trajectory starts with an impulse to protect audiences from "immoral" content and "sedition." As the industry began to change and society evolved, the Board bridged the gap. Their changes range from blurring alcohol bottles in Ford v Ferrari (so Indians won't see them drinking) to removing indications of Kashmir in Mission: Impossible – Fallout —the edits made by the CBFC represent more than prude; they are a vehicle of censorship with the express purpose of controlling not just what Indians see, but how they understand complex issues.

Where it started as a tool to "certify," it has become a tool to sanitise uncomfortable realities, in effect, a tool of suppression. It is less about public morality—if it ever was—and more about policing narratives that challenge some settled belief of the status quo, historical accountability, or political vulnerability. The notion of "protection" and "political expediency" appears to have become less abstract and much more imaginary.

Censorship on OTT Platforms

The revolutionary shift to streaming platforms initially allowed filmmakers an escape from the constraints of the CBFC; however, this oasis is increasingly in danger as the government's pressure and legal complaints attempt to rein in digital content to the same level of constraint as theatrical content.

One particularly notable example is Netflix's Leila, a new dystopian series that envisions a near-future India radically divided by extreme religious and political purity, as well as authoritarianism. Leila was attacked by right-wing groups who labelled it as "anti-Hindu," with politicians and activists calling for an investigation, banning, and stricter regulation of all OTT content. While the CBFC never formally censored Leila, CBFC censorship did not need to happen - the barrage of criticism and threats of legal action did enough to send a message to the creative community that there was no escape from (negative) consequences for their work, even in the digital context.

Likewise, Tandav (Amazon Prime) faced backlash for allegedly offending Hindu sentiments, mocking political hierarchies and disparaging caste. FIRs were filed across multiple states, and after Amazon officials met with Ministry of Information & Broadcasting officials, the makers of the show issued an apology and agreed to cut certain scenes voluntarily. Following the government's implementation of the IT Rules, 2021, and its oversight of OTT content, several platforms have voluntarily adopted self-censorship as part of the process. What was once self-regulation is now, at times, pre-censorship, as editors and creators sift through their scripts for any phrase, scene, or reference that may incite complaints and controversy.

Both series highlight a change, as OTT platforms initially began as an exciting new avenue for bold, disruptive Indian storytelling; however, given the pressures of the state and social milieu, they inevitably transformed into a more orthodox version of contemporary cinema. The chilling effect is real: the content of caste, sexuality, religion, and politics has been diminished, or in the case of marginalised realities, cut or removed. Legal uncertainty and the threat of organised outrage have led streaming platforms to censor as conservatively as the conservatively minded censor board member. This new regime of "soft censorship" is as ubiquitous and sporadic as traditional soft censorship in theatres has always been, and is increasingly influenced not only by bounded law but also by backlash and administrative consequences.

Anurag Kashyap and the CBFC: A Contentious History

Few filmmakers in modern India have taken on the challenge of moral policing as thoroughly as Anurag Kashyap. Kashyap's early film, a noir called Paanch (2003), received numerous objections on grounds of violence, drug use, and jargon, as did his subsequent films, Black Friday and Bombay Velvet; Kashyap's projects seem to be at odds with the CBFC's notoriously inconsistent ethics. Kashyap has referred to the CBFC as "rigged," stating that the decision-making process is opaque at best, arbitrary more often than not, and increasingly captive to political pressures and sensibilities. Recently, Kashyap has discussed the bizarre restrictions placed on character names (as seen in Janaki v. State of Kerala), or the muting of any reference that challenges myth, caste, or contemporary sensibilities.

Kashyap's critique is incisive: the CBFC, he writes, infantilises Indian audiences by not trusting them with "adult" decisions and misrepresents movies in their august role as didactic or moralistic. For Kashyap—like many others in the creative field—art's job is to "reflect" society, including its most unpalatable realities. The 'chilling effect' he has identified often results in essential films being changed, or withheld, and audiences ultimately consume the most 'sanitised version' and most innocuous parts of the story. Kashyap's public feuds, battles in the courts, and scathing commentary have made him the public face of pushback and fight against state censorship—yet, the system he fights remains.

CBFC Doesn’t Censor Harm, It Censors Discomfort

Interventions from the Board aren't usually a form of response to actual "harm." What they seek to speak to are instances of discomfort. To depict intimacy in a forthright manner is "too overt." To have names or scenes that concern caste injustice is "too political." Board-level cursing is muted, but the agency structures or humiliations causing that slur remain—uselessly retaining the status quo by not challenging it. Bizarrely depicted graphic violence, misogyny, or regressive tropes are sporadically unchallenged if they sit comfortably within recognisable, former or popular frameworks. The desire isn't to mediate trauma or trauma-like concerns, but load-shed and clean up anything that could discomfort or provoke thought or less control of narrative on behalf of dominant social expectations.

Consent is not the issue for the Board - visibility is. Censorship is not about “protecting” citizens, but concealing them from truly discomforting realities. The concern is that we end up with a cultural paradigm that fetishises cinema, not as a means of hard social engagement, but as a watered-down abstract pastel; the sharpness is nilled into a comfortable neutral. Creative risk becomes exceptional, not the norm; filmmakers self-censor, not just to avoid bans, but to protect themselves from issues like organised online harassment, loss of revenue, or legal complications. The Board is less about the actual custodianship of social good and more about the custodianship of the nation's emotional temperature. Therefore, in such a context, it isn't simply whether and how Indian art can thrive; it also concerns whether it can be provided as a critical mode of thinking at all.

Abolishing the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT)

Before 2021, creators still had an essential option if they felt aggrieved by the CBFC: they could appeal to the Film Certification Appellate Tribunal (FCAT). The FCAT offered relatively fast and inexpensive appeals, creating a buffer zone from overreach by the state and freedom for creativity. The Tribunal Reforms (Rationalisation and Conditions of Service) Ordinance of 2021 eliminated the FCAT as an option, leaving disgruntled creators with only the expensive, lengthy, and cumbersome alternative of litigation in the High Court. With backlogs in courts and high costs, most filmmakers now accept the CBFC's stern directives rather than try to push back or delay the release of their films. This new regulatory move has provided a significant power shift away from creators to the CBFC, while continuing to compound the risks and costs associated with creative dissent.

The Social Media Irony: Prasoon Joshi, Rang De Basanti, and ‘Would Swades Be Cut?’

Today's discourse is colored by both memory and irony. Prasoon Joshi, the poet-lyricist behind some of the gold-standard films of 'progressive' India, such as Rang De Basanti, now holds more power as the chair of the board responsible for these contemporary acts of censorship. Jokingly, people on social media note the irony that if Swades—a film that was unabashedly critical of poverty and corruption—were made today, the scene where the child sells water to Shah Rukh Khan's character might be removed for being "too real" or "unseemly." People joke, with bitter irony, that an offending contemporary censor would probably have an issue with much of India's cinema from the progressive years of the 2000s (and also inspired Joshi). This cyclical commentary reinforces the idea that Indian film censorship does not arise from principled beliefs, but rather the easy suppression of that which offends a constantly shifting notion of public decency.

Where Do We Go From Here?

India’s Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) was intended to categorise, not censor. However, over the years, it has become anything but. We do not now have a neutral certifier. We have a moral arbiter. It not only decides what audiences will be allowed to see but also decides what audiences should see. Instead of merely classifying the content for the audience, audiences suffered cuts, delays, and bans because the content took liberties with boldness, with politics, and with the adult. Often, cuts, delays, and prohibitions were imposed not because laws were being broken, but because sensibilities were being offended and the establishment was being challenged. This is not a classification. This is control.

As long as the CBFC operates as a censorship bureau, Indian filmmakers will continue to self-censor, cull their creative ideas, or play it safe because, as claimed, limits would be applied. This is about more than ideas; this is about constraining spaces for authentic and honest storytelling. If Indian cinema is to realise its full potential without constraint, we need to devise a rating system that will rate films free from external influences. Otherwise, stories will continue to emerge suppressed, eddying, and terrified.

The Takeaway

Filmmakers today no longer just fear the scissors of the CBFC – they expect them to wield them. Many authors now write with self-censorship in mind, diluting their vision to avoid criticism. We are not looking at the art that could be; we are looking at an art that has had its edges rounded off to pass muster.

The politicisation and bureaucratisation of film censorship are not unique to India. The United States has historical parallels in the Hays Code (1934-1968), where Hollywood was historically hamstrung by moralist watchdogs and self-censorship, preventing honest depictions of sexuality, race, or challenge for decades. Every authoritarian regime from Soviet Russia to Franco's Spain used censorship as a weapon to shape national identity, national history, and memorialise collective memory. Today in Russia and China, film authorities are still located in the centre. When films challenge the state narrative or draw attention to social fissures, authorities can simply erase them, pull them from distribution, or delay their release.

What’s new in India is the convergence of formal regulatory powers (CBFC and legal frameworks), informal political pressures (party-led campaigns, religious groups or social media backlash), and now, the systematic denial of affordable appeal through the High Courts. OTT is following suit and heralding a future where no platform is truly safe from uncomfortable truths. Artists and producers face the spectre of self-censorship; they forego scenes or entire subplots in anticipation of trouble, which reduces once-bold cinema to formulaic entertainment. Results are being felt in the audience space everywhere—whether in Mumbai, Moscow, or Beijing—where the industry is becoming less about art than about avoidance. When the business of image-making is policed by anxiety about “public order,” “national honour,” or the shifting sands of “hurt sentiments," the space for dissent, critique, or exploration in cinema can only diminish.

Film certification in India has evolved into a means of managing more than just audience morality. It has come to manage political fragility and political comfort. Censorship is rarely about harm; it is about protecting the powerful, the comfortable, and the stable from the discomfort of reality confronting them on screen.

2022 © Milestone 101. All Rights Reserved.